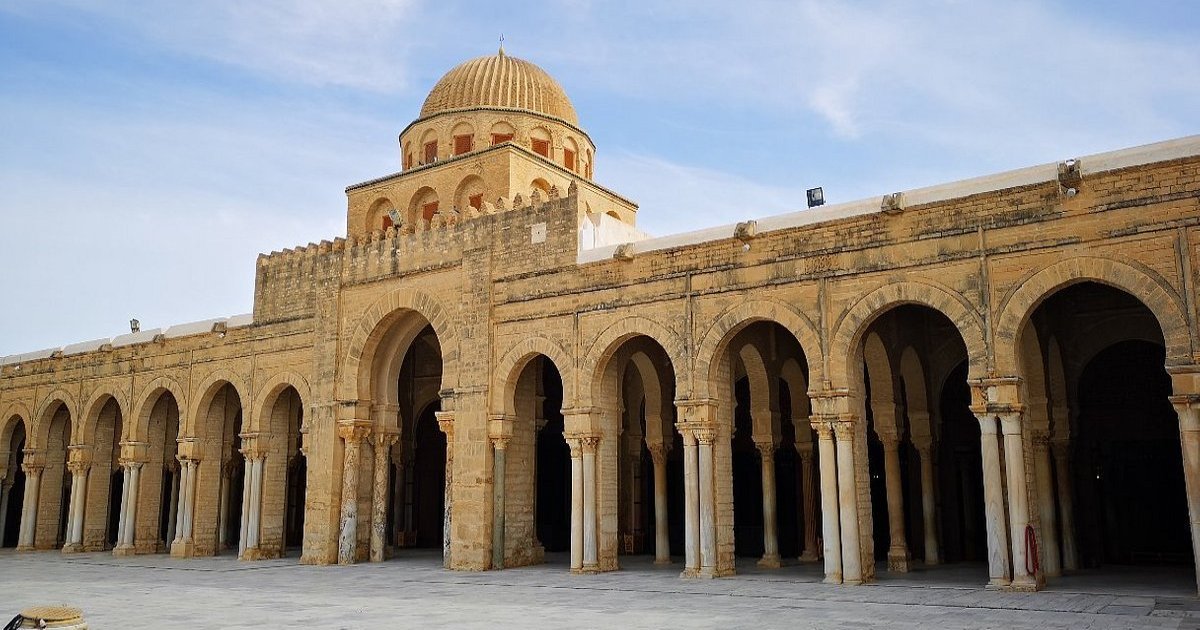

North Africa in the 7th century was not an easy site to create a new metropolis. It required fighting the Byzantines, persuading the Berbers, North Africa’s indigenous inhabitants, to accept centralized Muslim administration, and compelling Middle Eastern merchants to relocate to North Africa. So, in 670 CE, conquering commander Sidi Okba built a Friday mosque in what was to become the gear mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia nowadays. On the Muslim holy day of Friday, a mosque is utilized for community prayers. The mosque was an essential addition because it communicated that Kairouan would become a cosmopolitan city under strong Muslim leadership, which was a significant distinction for the time and location.

The great or grand mosque of Kairouan is an early version of a hypostyle mosque that also demonstrates how pre-Islamic and eastern Islamic art and elements were blended into Islamic North African religious architecture. The aesthetics represented the great mosque and Kairouan, and therefore its sponsors, as significant as the religious institutions, towns, and kings of other civilizations in this area, and that Kairouan was part of the expanding Islamic world.

About the Aghlabids

As Kairouan flourished in the 8th century, Sidi Okba’s masjid was restored at least twice. However, the mosque we see now is largely from the 9th century. The Aghlabids (800-909 C.E.) were the semi-independent leaders of most of North Africa. In 836, Prince Ziyadat Allah I demolished much of the older mudbrick construction and reconstructed it in more durable stone, brick, and wood. The main building, or sanctuary, is sustained by a series of columns, and there is an outdoor courtyard, which is typical of a hypostyle layout.

Another Aghlabid king expanded the courtyard entry to the prayer room in the late 9th century, adding a dome over the main arches and gateway. The dome underlines the centrality of the Mihrab.

The dome is an adopted architectural feature from Roman and Byzantine construction. The tiny openings in the dome’s drum above the Mihrab area admit natural light into the usually dark inside. Rays hit the most important part of the mosque, the Mihrab. The drum is supported by squinches, little arches ornamented with shell over rosette motifs reminiscent of Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad Islamic art. Per the architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell, the stone dome is made up of 24 ribs, each with a little corbel at the base, giving the dome the appearance of a sliced cantaloupe.

About the great mosque of Kairouan

Other structural aspects connect Kairouan’s great mosque to past and present Islamic religious complexes, as well as pre-Islamic monuments. They also demonstrate the great mosque of Kairouan’s religious and secular significance. The mosque of Kairouan, like other central open mosques such as the Prophet’s mosque in Medina, is essentially rectangular. It has a T-plan due to wider lanes going to the Mihrab and along the qibla wall. Repurposed Roman and Byzantine columns and capitals hold the sanctuary ceiling and courtyard porticos.

The bottom section of the Mihrab is embellished with decorative marble panels with floral and geometric vine motifs. Though the overly ornamented Mihrab is distinctive, the panels come from Syria. Iraqi lustre tiles surround it. They also include stylized floral motifs similar to those seen in Byzantine and eastern Islamic art.

The Minbar of the great mosque of Kairouan

The mosque features a 9th-century Minbar, a short wooden platform where the weekly sermon was given, as it was used for Friday prayer. It is considered to be the oldest wooden Minbar still standing. Like Christian pulpits, it made the prayer presenter more visible and vocal. The Minbar provided both religious and secular objectives since a ruler’s legitimacy could be determined by the mention of his name during the sermon. The Minbar is constructed of teak brought from Asia, a costly material that demonstrates Kairouan’s commercial reach. The side of the Minbar nearest to the Mihrab is sculpted with ornate latticework with vegetal, floral, and geometric forms reminiscent of Byzantine and Umayyad styles.

The Minaret of the grand mosque of Kairouan

The Minaret, or at least its lower half, originates from the early 9th century. The large square Kairouan Minaret is around 32 meters tall, or over one hundred feet, and is one of the tallest buildings in the area, maybe influenced by Roman lighthouses. In addition to serving as a site to call for prayers, the Minaret serves to identify the mosque’s existence and position in the city, as well as to assist establish the city’s religious identity. Because it was located slightly off the Mihrab axis, it further emphasized the significance of the mihrab.

Because it was located slightly off the Mihrab axis, it further emphasized the significance of the Mihrab.

The Maqsura of the great mosque of Kairouan

The mosque was renovated after the Aghlabids, demonstrating that it remained spiritually and socially prominent even after Kairouan declined. A Zirid, al-Mu’izz ibn Badis (ruled 1016-62 CE), authorized the construction of a timber Maqsura, an enclosed chamber inside a mosque intended for the monarch and his friends. The Maqsura is made of cutwork timber screens that are topped with bands of carved abstracted plant patterns placed into geometric frames, Kufic-style script inscriptions, and merlons that resemble the crenellations of a castle wall. Maqsuras are thought to signify a society’s political instability. They pick a ruler from among the worshipers. As a result, the enclosure and its inscription both safeguarded lives and confirmed the status of those let within.

The Hafsids strengthened the mosque in the 1300s by adding buttresses to sustain crumbling external walls, a procedure that was followed in succeeding years. Caliph al-Mustansir rebuilt the square and constructed massive gates, such as the domed Bab Lalla Rejana on the west, in 1294. Later centuries saw the construction of more gates. Ornately carved panels inside and outside the mosque served as billboards, announcing whose patron was in charge of building and repair.

A center of knowledge

The great mosque was at the heart of Kairouan activity, expansion, and grandeur, both physically and metaphorically. Though the mosque is today near the northwest city walls, when Sidi Okba created Kairouan, it was probably closer to the heart of town, between the governor’s home and the main road, a symbolically significant and physically visible section of the city.

By the half century, Kairouan had developed into a bustling community with markets, agricultural imports from neighboring cities, water cisterns, and textile and pottery production districts. It served as a governmental capital, pilgrimage destination, and intellectual hub, notably for the Maliki school of Sunni Islam and the sciences. The grand mosque had 15 thoroughfares going from it into a city that resembled Baghdad, the center of the Islamic empire during Kairouan’s reign. It was one of, if not the, biggest structures in town as a Friday mosque.

The great mosque of Kairouan was a community edifice built along routes in a city with thriving economic, intellectual, and religious activity. As such, it played an essential role in reflecting cosmopolitan and urban Kairouan, one of the earliest towns formed under Muslim authority in North Africa. Even now, it reflects its period and site of construction.